Con Artists Use Age-Old Scams On The Crypto Frontier: Part-4

Blockchains’ have vast potential to solve critical problems in property ownership, academic records, materials sourcing, and even personal identity. As with core technologies like the steam engine and the internet in their early days, we have yet to imagine the full extent of blockchain’s benefits.

Welcome to the fourth and final essay in our series on fraud in cryptocurrency and decentralized finance (DeFi). If you're new to the series, start with Part 1. Technology does not change humans, but it can make what we do 10X bigger and faster. We can be human at warp speed, including when we commit fraud.

Crypto Makes Embezzlement Bigger And Faster Than Ever

Embezzlement may be the world’s oldest crime, but cryptocurrency and other DeFi tools make it exponentially faster and more lucrative. A person embezzles when, in a position of trust, he takes other persons’ property and uses it for himself. Before writing and probably even before language, a tribesman somewhere held his clan’s trust to guard their food. Instead, he ate some then claimed a rat had stolen it. He never mentioned that he was the rat.

Grifters embezzle hundreds of millions of dollars in mere seconds on the unregulated crypto landscape. Sometimes they use tactics as old as that tribesman saying, “the rat took the food." Other times, they out-smarting the smart-contracts defining who owns the food in the first place. Always, the grifters are narcissistic, remorseless, and passionate about manipulating people: they epitomize psychology’s “Dark Triad.”

Two Embezzlements. One Old. One New. Both Old-School.

When financial companies embezzle clients’ funds they run pretty much the same plays, regardless of the technologies used.

Charles Keating, the owner of Lincoln Savings and Loan (S&L), was the face of the 1980s S&L Crisis. The Los Angeles Times described Keating as "a businessman without apparent peer in Arizona in terms of riches, clout, and color.” (Furlong 1988) He owned a palatial family compound, a helicopter, and three corporate jets including one with gold-plated bathroom fixtures. He flew Mother Teresa in his helicopter to visit native American tribes in the southwest.

One tiny problem: Keating used depositors’ money to pay for it all. Federal investigators accused Keating of running his businesses as a personal piggy bank, ransacking them for a series of risky investments.

Keating contributed $ 1.5 million to five United States Senators. The so-called “Keating Five” pressured federal regulators to back off from Lincoln Savings and Loan. “I have never met a man with more political clout in my life,” said one high-ranking S&L regulatory official in 1988.

Clout couldn’t hide a baked balance sheet: Lincoln went bankrupt in 1989. 20,000 depositors, many of them pensioners, lost their savings in accounts that they did not know were uninsured. Taxpayers footed a $3B bailout and Keating spent five years in prison for fraud. Regulators auctioned off his estate.

The Lincoln S&L story is similar to what we are learning about the stunning multi-billion-dollar collapse of FTX. Until its November 11, 2022, bankruptcy it was the third-largest cryptocurrency exchange. You can find details of FTX’s alleged misdeeds in numerous articles like this one. This Wall Street Journal video also gives a clear explanation:

The bottom line: FTX’s depositors and clients are missing $8 billion.

FTX’s core business enabled clients to buy and sell cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin. Clients could also trade complicated assets called derivatives based on those cryptocurrencies. Importantly, clients could also keep accounts at FTX to hold their cryptocurrency and “fiat money,” the crypto community’s name for currencies like U.S. dollars and yen.

Like Lincoln S&L, FTX had a charismatic CEO. Sam Bankman-Fried, or “SBF,” was hailed as “The JP Morgan of this generation.” He lived in a $40 million flat in the Bahamas. Like Charles Keating, SBF was a major political donor bestowing a reported $40 million to candidates in the 2022 United States midterm elections. SBF was a regular Capitol Hill and White House visitor for cryptocurrency regulation discussions. Given FTX’s spectacular implosion, you wonder what kind of regulation he was angling for.

John Ray III, FTX’s new CEO (i.e., the Chief Cleanup Officer), summarised FTX's con to Congress on December 13, 2022. "This (FTX) is really old-fashioned embezzlement. Taking money from others and using it for your own purpose. Not sophisticated at all, sophisticated perhaps in the way they were able to sort of hide it from people, frankly right in front of their eyes. But this isn't sophisticated whatsoever, it's plain old embezzlement. Old school."

While blockchain-spawned cryptocurrencies underlying FTX’s scheme are modern, the grift is classic. Lincoln S&L and FTX imploded in different centuries, had founders separated by multiple generations in age and experience, and ran in industries sitting at opposite ends of the risk spectrum. Yet they used the same playbook and got the same results.

Legal Embezzlement Through Crypto

I wrote back in Part 1 of this series that fraud may be the oldest industry disrupted by cryptocurrency. It’s a crook’s perfect storm: instantaneous, irrevocable, borderless transactions with anonymous parties using complex software with virtually no oversight.

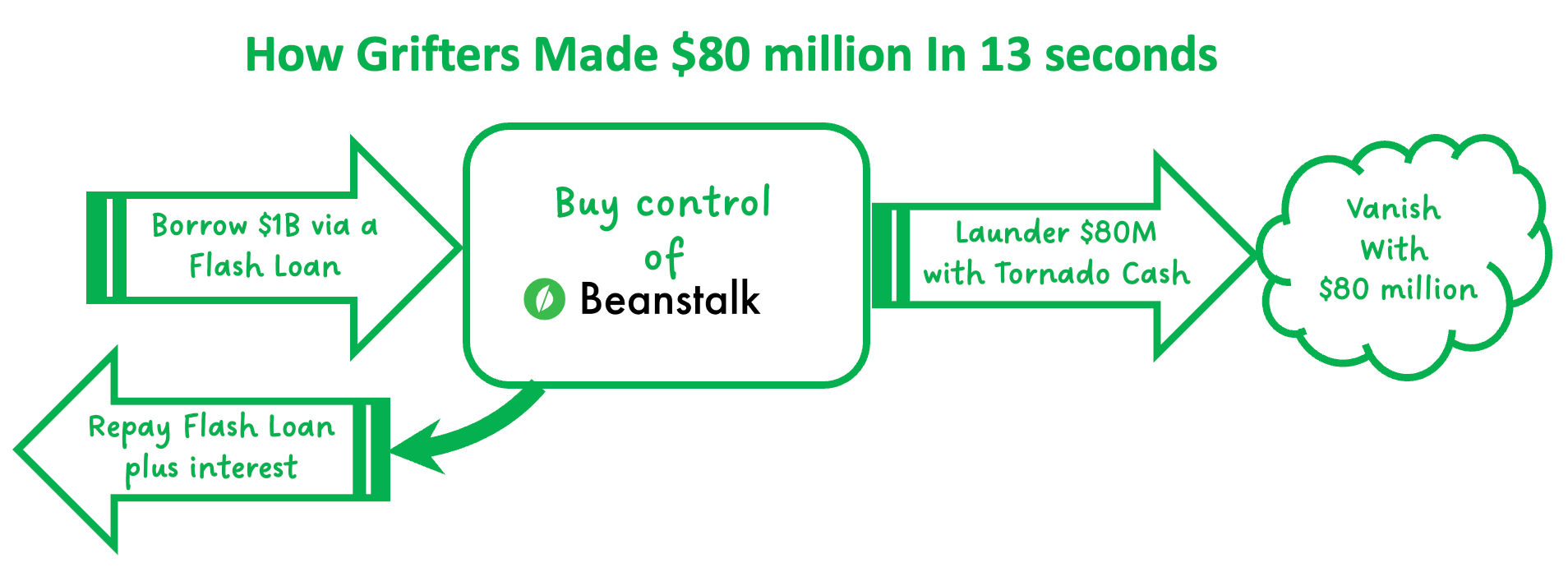

One of 2022’s most clever crypto embezzlements leveraged all those features to lift $80 million from clients and investors. It was blindingly fast and probably legal.

On April 24, 2022, owners of “Beans,” tokens for the Beanstalk Farms distributed autonomous organization (DAO), found their accounts drained. Scammers took out a $1 billion “flash loan,” where cryptocurrency is loaned and repaid in seconds, to buy a controlling interest in the DAO. Once the grifters had voting control of Beanstalk, the DAO's software let the new “owners” whisk clients' funds away into their anonymous wallets. In cryptocurrency and Decentralized Finance, they say, "Code is Law," the scammers used the software exactly as it was designed to be used. They used some of their loot, uhm, “assets,” to pay interest on the flash loan, then made off with $80 million worth of cryptocurrency.

In 13 seconds, about the time it takes to down a pint or send a text, some jerks took out a loan, hijacked a company, gave themselves the clients’ assets, repaid the loan with interest, and vanished with $80 million.

As we learned in Part 1, pulling off a con requires a Mark or sucker, the sucker’s confidence, and a getaway plan. The Beanstalk scam had all three: crypto speculators, their belief in indelible digital asset ownership via a blockchain, and crypto’s borderless global anonymity.

Here is how the Beanstalk con artists covered their tracks. A key blockchain database feature is that every transaction is traceable. Some clever coders developed a foil for such transparency, a “cryptocurrency tumbler.” It’s an elegant concept. You deposit your crypto into the tumbler. The tumbler mixes together deposits from thousands of users. You then take the same amount of crypto out of the tumbler using a different wallet, with the tumbler using cryptography to ensure there is no trace between your deposit and your withdrawal. It’s a lightning-fast digital getaway car.

The Beanstalk scammers used the Tornado Cash tumbler. The U.S. Treasury Department blacklisted Tornado Cash in August 2022 making it illegal for U.S. citizens to use. Because crypto cons can be launched by any clever person with an internet connection, such U.S. government action hardly limits global access to Tornado Cash. The story isn’t over: U.S.-incorporated crypto exchange, Coinbase, has funded a suit against Treasury to lift its ban. Their argument is that the technology isn’t the problem, the people who use it to launder illicit crypto are.

Regulation Is Not a Dirty Word

Following the 1929 stock market crash and devastating bank runs at the start of the Great Depression, millions of people stopped using the financial system. They literally hid their money in mattresses. Regulations like the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act and the 1934 Securities Act give us ordinary people two key assurances: A) There are rules, and B) Grifters who break those rules like Charles Keating, William Duer (from Part 1), and Michael J. Meehan (from Part 3) will face penalties and market banishment.

Regulation is not a dirty word. Without basic safeguards average consumers, who will never learn about cryptographic keys and hash tables, won’t trust crypto. They won’t use it, and its market will remain limited to speculators. Instead, crypto investors should see independent regulation as necessary for the industry to thrive.

New Tech Does Not Mean New Humans

Cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and other blockchain-based DeFi tools are made and used by humans. Hyper-clever grifters are always looking for exponentially safer and more lucrative cons. This series reiterates timeless rules for avoiding scams:

1. If something seems too good to be true, it isn’t.

2. The First Law of Marketing: It’s relatively easy to get people to believe something that they already want to believe.

3. Grifters are jerks: remorseless, Machiavellian, and manipulative (the Dark Triad). By ignoring Rules 1 and 2, Marks/suckers are often willing participants in a scam.

We complain about old industries like banking being impersonal, opaque, slow, and expensive. Believing that cryptocurrency will magically solve these problems by replacing institutions with unregulated self-managing software-controlled organizations ignores history and human nature.

Final Word: The Core Tech Works and Can Drive Positive Impact

Tech is never a solution unto itself. What matters is how we use it. Blockchain tech works. It does what it's designed to do with jaw-dropping elegance.

Blockchains are data bases, stores of records of any sort from simple numbers to complex software programs. The cool part is, when properly designed and used, a blockchain is a permanent, unchangeable, transparent record of everything that’s ever been put into it, who put it in, and when.

I’ve written about blockchains’ vast potential to solve critical problems in property ownership, academic records, materials sourcing, and even personal identity. Blockchain is young and crypto is an early application. As with core technologies like the steam engine and the internet in their early days, we have yet to imagine the full extent of blockchain’s benefits.

Works Cited

Faife, Corin. “Beanstalk cryptocurrency project robbed after hacker votes to send themself $182 million.” The Verge, 18 April 2022, https://www.theverge.com/2022/4/18/23030754/beanstalk-cryptocurrency-hack-182-million-dao-voting. Accessed 3 January 2023.

FURLONG, TOM. “Developer With a Cause Battles on Many Fronts.” Los Angeles Times, 13 March 1988, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-03-13-fi-1784-story.html. Accessed 13 January 2023.

Stanley, Isaac, et al. “FTX's Bankman-Fried donated about $40M this political cycle. Here's who benefited.” The Washington Post, 14 December 20

Have you checked out the feeds on https://openexo.com/feed/exo?

ExO Insight Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.